Paintings research 14/5/2024

Who was Ella Jacob?

I was recently asked to examine a large painting in the small church of All Saints, Chicklade. Wiltshire. It is a large triptych of the Crucifixion with Saints on either side and is a copy of a fresco in a church in Florence by Perugino (1445-1523). The painting was discoloured by years of dust but was in relatively good condition. There was evidence of some previous restoration to strengthen outlines of figures and regilding of halos. However, what intrigued me was the artist. The only information I was given was that it was by Eleanor (Ella) Jacob and had been in the church since 1888. A quick search on the internet mentioned an earthenware vase with carved decoration by Ella which is in the Victoria and Albert Museum and their records indicated that it was a student piece from her time at the Salisbury School of Art. However, there was no information about her paintings.

Fortunately, a genealogist, David O’Connor, helped to unravel the mystery. His search through birth, death and marriage records as well as contemporary newspapers and other information in the national archive records began to build a picture of this elusive artist. Within three weeks he had unearthed over 80 historical documents. Her family lived in the Cathedral Close in Salisbury, her father, John Henry Jacob, was a Justice of the Peace, the family was wealthy and well connected in Wiltshire. Ella attended the Salisbury School of Art and subsequently exhibited her paintings in exhibitions in Salisbury, London, Bournemouth, and Dorchester. She also produced painted scenery for theatres in Trowbridge and other venues.

Further research into the family provided a link to Anton Jacob, the last direct descendant of John Henry Jacob, Ella’s father. During a visit to his house, we unearthed John Jacob’s diaries of the late 19th century and letters to Edward Jacob, Ella’s brother who had moved to Sweden. Ella often visited her brother as they shared an interest in painting and through this link, his descendants have been able to provide images of her watercolours. One is of a scene in Italy which was the first definite link to her travelling there. Exhibition catalogues listed scenes from other European countries, but I have yet to find diaries or letters about her travels in Europe.

Although I began to collect information about her paintings, there were unanswered questions, particularly who commissioned this large painting and how did she manage to produce such a good copy as the original was in Italy? In 1849, the Arundel Society was established to promote the arts by publishing chromolithographs of great European paintings, particularly Italian. We discovered that Edward Kaiser had produced a small watercolour of the painting for the Society which was subsequently made into a chromolithograph. These were available through print sellers such as Brown and Co in Salisbury and she may have purchased a print from them.

I was curious to know the connection between Ella, her painting, and the church. A search of church faculties did not provide any information. As her father was a canon at Salisbury Cathedral, his connection may have enabled him to arrange for Ella to undertake the painting for the church. However, there is no correspondence in the Cathedral archives to confirm this theory. Ella was well connected to local aristocratic families such as the Pembrokes and the Fitzwilliams and research into their archives might provide more information.

On her death, Ella left her fortune and personal effects to her twin sister, Edith, and Edith’s deceased daughter’s second husband, Francis Alfred Spencer. The search has now begun to trace descendants who might have inherited any letters, diaries, sketches or paintings belonging to Ella which might answer my remaining questions.

As more information about Ella and her painting is discovered, it is hoped that funds can be raised to conserve her painting and give Ella the recognition she deserves. Like so many amateur female artists of the 19th century, their artistic achievements and lives remain poorly documented.

Post created by Christine Sitwell 14 May 2024

…a little painter in the house cleaning paintings

Christine Sitwell reflects on her recent online talk for the Institute of Conservation (ICON) entitled, There is a little painter in the house cleaning paintings.

The title of the talk was taken from a letter written by Theresa Parker to her brother, Lord Morley (owner of Saltram House near Plymouth, Devon) in 1795. In her letter she states, that in the house are Lord and Lady Fortesque, Lord and Lady Worcester and a little painter who is in the house cleaning pictures. The little painter was Timothy Collopy, an Irish artist who resided in London after studying in Rome and eventually became a picture cleaner. This letter stimulated my curiosity in discovering information about the domestic arrangements for the care of paintings and the role of the restorer in National Trust properties while they were still in private ownership before eventually being acquired by the National Trust.

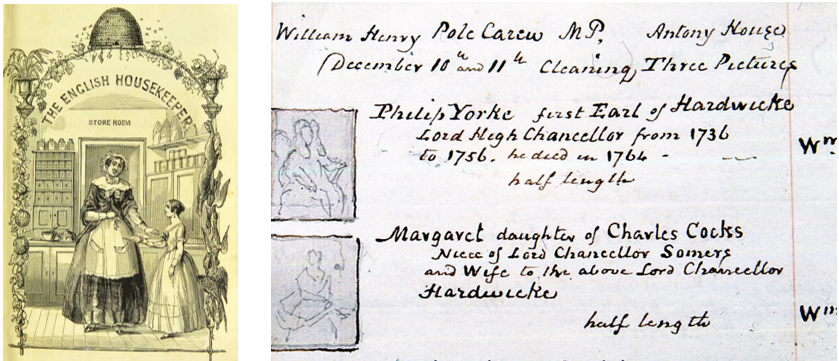

In the 18th and 19th centuries, the domestic management of the care of the household collections, including paintings was often the responsibility of the mistress of the house or the housekeeper. Katherine Windham, the mistress of Felbrigg Hall from the early 18th century, kept a notebook on household management in which she notes, to sift some wood ashes very fine, mix with fair water and wash your pictures well over with it. A number of books on housekeeping such The Housekeeping Book by Susannah Whatman and Ann Cobett’s, The English Housekeeper, were also available which not only provided information on dusting but also preventive measures such as covering paintings with linen during the periods when the house was unoccupied.

By the 19th century, the specialised trade of the restorer was well established and authors such as Manfred Holyoake, Henry Merritt and Henry Mogford, wrote books on the restoration of pictures. They described the perils facing paintings inflicted by neglect, the environment or overzealous treatment.

One of the best documented restorers in the 19th century working in National Trust properties was Henry Restra Bolton. His account book and invoices provide an interesting record of the restoration work he undertook at Saltram by listing the number of paintings, the treatments and materials used. Although the descriptions are rather brief – cleaning and restoring or cleaning and varnishing - the numbers treated daily or weekly give an indication of the type of treatment. The majority of paintings which were treated in situ were surfaced cleaned to remove dust and smoke, revarnished, and where necessary, retouched to disguise paint losses or large cracks. Henry also worked at Antony House and Petworth.

Household manuals and invoices are valuable sources of information on past cleaning methods.

Henry died in 1871 and the next restorer at Saltram was Horace Buttery. There were various generations of the Buttery family who undertook restoration at numerous properties in the National Trust well into the middle of the 20th century. Restoration like other businesses was often a family affair and another important family descends from Edward Holder who worked at Petworth in the early 19th century. Although there are invoices related to their work, the details are limited simply identifying the painting and a brief description such as cleaning, lining or varnishing with little information about the materials used.

Petworth House in West Sussex provides another example of extensive information about restoration practices from the 19th century onwards and the role of the owner in deciding who would undertake the work and their remarks on the quality of the restoration work. The 20th century is particularly interesting as Petworth House and parkland were given to the National Trust in 1947 and upon the death of Lord Leaconfield in 1952, his nephew and heir offered a large proportion of the paintings collection to the Trust in lieu of death duties.

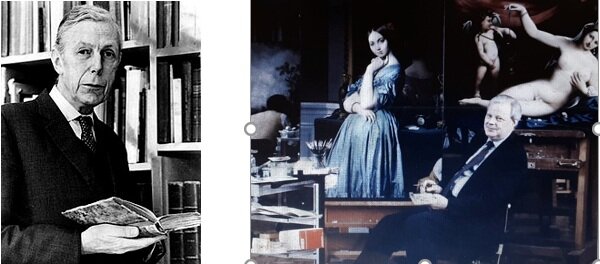

Anthony Blunt, Surveyor of the Queen’s Collection was the Trust’s Honorary Adviser on Paintings, and it was his task to assess the quality of the paintings and arrange their conservation treatment along with Bobby Gore of the National Trust to fulfil the Treasury’s requirements for the transfer. With so many paintings needing treatment, Blunt selected a range of restorers including the firms of Buttery, Holder and Vallance (who inherited Holder’s business upon the death of William Holder). However, Blunt soon realised that a large number of paintings would need to be treated in situ and commissioned the young John Brealey, who would later become the Head of Paintings Conservation at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, to undertake the work.

Anthony Blunt (left) and John Brealey (right) at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Brealey was to spend months at Petworth working on 50 paintings and Blunt records that Brealey and I were alone in the house and in the evenings sat in the white library – the only room with a fire. This was no doubt a great comfort as there was no heat in the house. Brealey recorded that it was marvellous working in the Marble Hall, which was his studio, with the deer coming up to the window in the early morning.

The monumental effort to conserve the paintings at Petworth was a turning point for the Trust. Many country house owners and the restorers employed by them ensured the preservation of paintings, but that transfer of responsibility to the Trust has ensured a systematic and sustainable approach which ultimately led to the establishment of a conservation section devoted to the care of paintings and other contents.

Post created by Christine Sitwell 6 August 2021